Mini Masterclass is a bite-sized monthly column by Erin Karbuczky for writers hungry to deepen their craft, shift perspective, and try something new. Each installment offers an actionable lesson—grounded in real examples and fresh thinking—from the worlds of fiction, memoir, poetry, pop culture, and beyond.

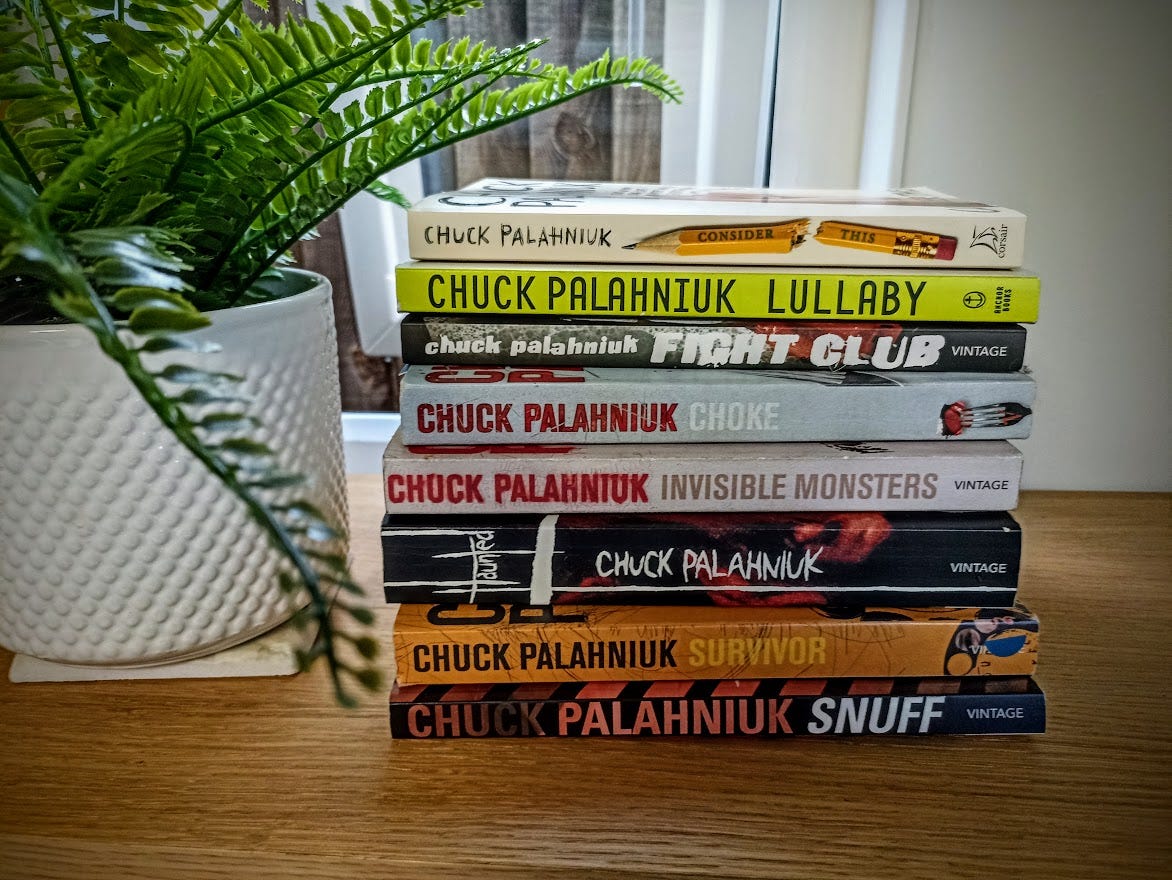

Many of us are familiar with cult author Chuck Palahniuk’s craft book slash memoir, Consider This: Moments in My Writing Life after Which Everything Was Different. It has been recommended to me multiple times, and with good reason. The approach to craft in this text is easy. Not easy in the sense that it is lazy, but because it is easy for the reader to actually understand what the hell Chuck’s talking about. The tips are practical and implementable.

And it is this ease with which the craft is presented that makes this method easy to teach and to discuss in a writer’s group setting, so everyone is on the same page about their work (no pun intended!).

In February of 2020, I signed up for a writing class at the Attic Institute in Portland. It wasn’t my first class at the Attic, but it was my first class under Joanna Rose. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit and all in-person classes were cancelled, the Attic pivoted to online learning rather than cancel all their classes. Logging onto Zoom that first day was petrifying (Zoom is still petrifying if I’m being honest), but by the end of class, I was so glad I had attended. On that first day, Joanna handed out a list of terms we would use to discuss each other’s writing. Having a guide for critiquing was essential - most of us had never been in a formal critique setting before.

By the time the class ended for good, we all decided to do another round together. And when that was over, I reached out to people from the class that jived together, and started a critique group. We decided to use the terms from Joanna Rose’s class to keep a language we all understood for discussing our work.

I started to do some research using what information Joanna had given us, and that research revealed a rich history of a group called Dangerous Writers, of which both Joanna and Chuck were a part of.

If you have read work by any of the following writers (non-exhaustive), then you have read writing influenced by Tom Spanbauer’s Dangerous Writing:

What is the essence of Dangerous Writing, and how did it start?

Inspired by the teachings of writer Gordon Lish, Tom Spanbauer came to Portland in 1990 and began teaching a group of eager, talented young writers at his house, including some of those mentioned above. The writers spent a lot of time together critiquing each other’s work, gardening and renovating Tom’s home (seriously), and dining together. All of the writers were hungry to share and publish their work, and many of them have published. But what is most interesting about the group called Dangerous Writers is how it bloomed and cemented itself in the lore of American writing. Not only did many of the writers go on to publish, but a fair number of the group eventually broke off to mentor and teach their own cohorts, and they, in turn, mentored and taught their own. Therefore, there are multiple branches now, and while all carry on the same sentiments, they each have their own interpretations, adaptations, and terminology based on Tom’s original teachings.

Chuck calls it minimalism. But Tom Spanbauer considered Dangerous Writing as the use of fiction to lie in order to tell the emotional truth, to get to the heart of the matter, to the bone. It should be noted that Tom was a queer writer, and Dangerous Writing was in part informed by that. However, Dangerous Writing is for everyone.

In an article written for Nailed Magazine, Tom said,

“I start with something true, something inside me that won’t let me be, and then I build a fiction around it.”

In other words, you lie about the facts in order to tell the EMOTIONAL truth of the story. You are writing with your heart rather than your brain.

He went on to say that:

“The writer…puts on a mask [and tells the truth], [creating] tension and drama where in ‘real life’ there was no tension and drama. [Dangerous Writing] distorts the truth. The writer weaves the universal within the ordinary.”

Say that your mother left when you were a child. Maybe it didn’t cause much drama in your outer life, but inside you were profoundly affected. Dangerous Writing would entail taking that kernel of emotional truth, and building a world and events that showcase that truth. Perhaps in the story, your mother appears to you each evening as a goldfish swimming in outer space, giving you life lessons and telling you how much she misses you and why she had to go away. Dangerous Writing can be both realistic and fantastical. Dangerous Writing understands that truth can be emotional more than factual.

Here I will share with you some of my favorite learnings from my time as a Dangerous Writer. I am using a blend of what I learned from Joanna Rose and Chuck Palahniuk below and sometimes infusing my own words with theirs, as that is what Dangerous Writers do.

Authority: Instead of establishing your authority on a topic by infodumping, use your character to establish authority through the way they think and speak. For example, if your character is a bird expert, they may describe objects and people using language and phrasing normally reserved for birds. Another way to do this is with carefully crafted and expertly placed lists. A character who is an expert on baking may share recipes as part of the narrative, or make a list of the top ten cheesecakes they’ve ever had as a covert way to further the plot and give more backstory. The possibilities are truly endless - authority is using your character’s unique perspective on the world to the fullest advantage.

Received Text: Received text is a cliche, or a cultural phrase that is ingrained inside of us. Rather than using cliches, use your authority to make your own language within your world.

Horizontal and Vertical: Horizontal is the events of the story as they take place (in chronological order). Vertical is the memories and feelings the events evoke, or as Chuck puts it, the “increase in physical, emotional, and physiological tension.” So, when a significant event takes place in the novel, how can you branch out from that event like an exploding bomb, and create tension using the character's memories and feelings?

Sacred Objects: Also called Love Your Objects, or Recycle Your Objects, these are the talismans your characters continuously, consciously, and subconsciously reach for. Perhaps your character has a piece of jewelry; let’s say a ring they twist around their finger when they get nervous. Perhaps that ring goes missing and sets off a course of events. Or your character may reach continuously for a worn pack of tarot cards with a backstory that informs the events of the current story. Here is a prompt I got from Your Daily Writing Prompt and adapted for myself:

Go back to a previous chapter of your novel (or an early passage in your short story, etc) and find a random object. Then assign that object meaning in your current passage so that it becomes a clue or serves a new purpose. Examples: an old valentine, an old tube of mascara, or the jewelry or tarot cards above.

On the Body: Be sure to focus on physical sensations within your character whenever possible. Ground your reader in the body of the character so they experience the world as their own. Your character is not a floating head. Make them as real as you can!

Clock and Gun: I LOVE THIS ONE! A clock is the deadline your character is racing against, and a gun is the reveal of a secret or a lie. Both will create supreme tension. One way you can do this is when you plot your story, make an event at or toward the end that is a deadline for your character - this will keep you from meandering, and keep the character on edge as if they don’t complete their mission by that date, there will be negative consequences. Then, throughout the novel, you can devise ways to keep your character off track or behind on their goal. With the gun, or the secret/reveal, you have something in your back pocket that can create a ripple effect throughout the whole story when you choose to reveal it, creating more tension.

Of course, there are Dangerous Writing rules that I do not love, such as avoiding “latinate” terms (purple or flowery prose) or figurative language. However, I do appreciate the sentiment that removing these words and language from your writing will help you think harder about how to phrase things and why. I also know, both as a student and teacher, that it is important to learn the rules before you spend the rest of your time breaking them in your own special way.

There is so much more to learn from Chuck’s book, and there is no way to cover it all and do it justice in a single article. I bet your local library has a copy! They may also have some books by the Dangerous Writers or Spanbauer himself.

Tom Spanbauer passed away this past September. He never knew me, but he taught me so much through his students and their interpretation of his work. I am forever grateful to him and I’m so glad his legacy lives on.

Have you ever had a writing teacher or mentor who profoundly affected the way you write or think about writing? Do you still have a relationship with them? What did they teach you that you still use to this day?

Are there emotional situations in your past or present that perhaps feel too raw to write about directly? Can you disguise one or more of those situations so that you can write about the emotional truth of it all?

What writing rules do you like to break, and why?

What do you wish you did more of in your own writing? Is there a certain flair or stylistic aspect you are holding back on because it’s against the “rules”?

Where in your current WIP can you use Chuck’s/Dangerous Writing techniques to sharpen the story?

PS - I have a series on my Substack called Writer’s Notebook Wednesday in which I share writing prompts similar to the above. My prompts are there to help you dig deep into your writing and your psyche, to get to the how and why and heart of it all. My Substack and prompts are free.

Please share in the comments if there are mentors (whether you’ve met them in real life or not!) who have shaped your writing life and how. I’ll go first - anything VE Schwab says is gospel to me!

Good quick summary! Chuck’s craft essays and generosity in sharing and promoting other’s work is the ideal idea of established author, how I hope to be when I make it big.

From Chuck, I read Craig Clevenger, who also taught practical writing tips, like dialogue should reveal who has power and that trait can be transferred and therefore should be dynamically passed amongst speakers as they reveal/threaten/promise/etc. during their conversation. Craig introduced me to Sara Gran, who taught me, “write the most interesting parts of your story first. Then write the less interesting parts. Leave out what’s unnecessary.” Sara, when asked what book she recommends the most, introduced me to Charles Portis’ True Grit, which I’m still assessing the lesson (strong voice? Thrilling action? Never a character alone?)

Love this! Such a thought-provoking way to go about writing & revising -- and such a great teaser to dig in to the approaches further. Thank you!