Mini Masterclass is a bite-sized monthly column by Erin Karbuczky for writers hungry to deepen their craft, shift perspective, and try something new. Each installment offers an actionable lesson—grounded in real examples and fresh thinking—from the worlds of fiction, memoir, poetry, pop culture, and beyond.

You may have guessed by now, if you’ve read my previous masterclasses, that I am interested in how different elements of fiction, and parts of the writing process (such as theme and conflict), are connected in different ways than we typically talk about when we talk about writing. Grouping these elements together helps me understand how different parts of a story work together, rather than as separate parts, and I hope they’ll help you do the same!

Before we begin, take a moment to get comfortable, get a glass of your preferred beverage, and maybe a snack and a pen that has plenty of ink. There are a lot of prompts today for your writer’s notebook.

Today, we are looking at the point of view, structure, and genre. Although I’ll break them down piece by piece, the point of view, structure, and genre of a story are interconnected, and viewing them as such will help you make decisions that are in service of your story.

So why are these three elements grouped together? Simply put, they are all ways in which you orient the reader in the world of your story, and organize your story for an optimal reading experience.

I encourage you to answer these questions even if your novel is already in progress - the answers can change or deepen your relationship to the story and how you want to tell it.

Point of View

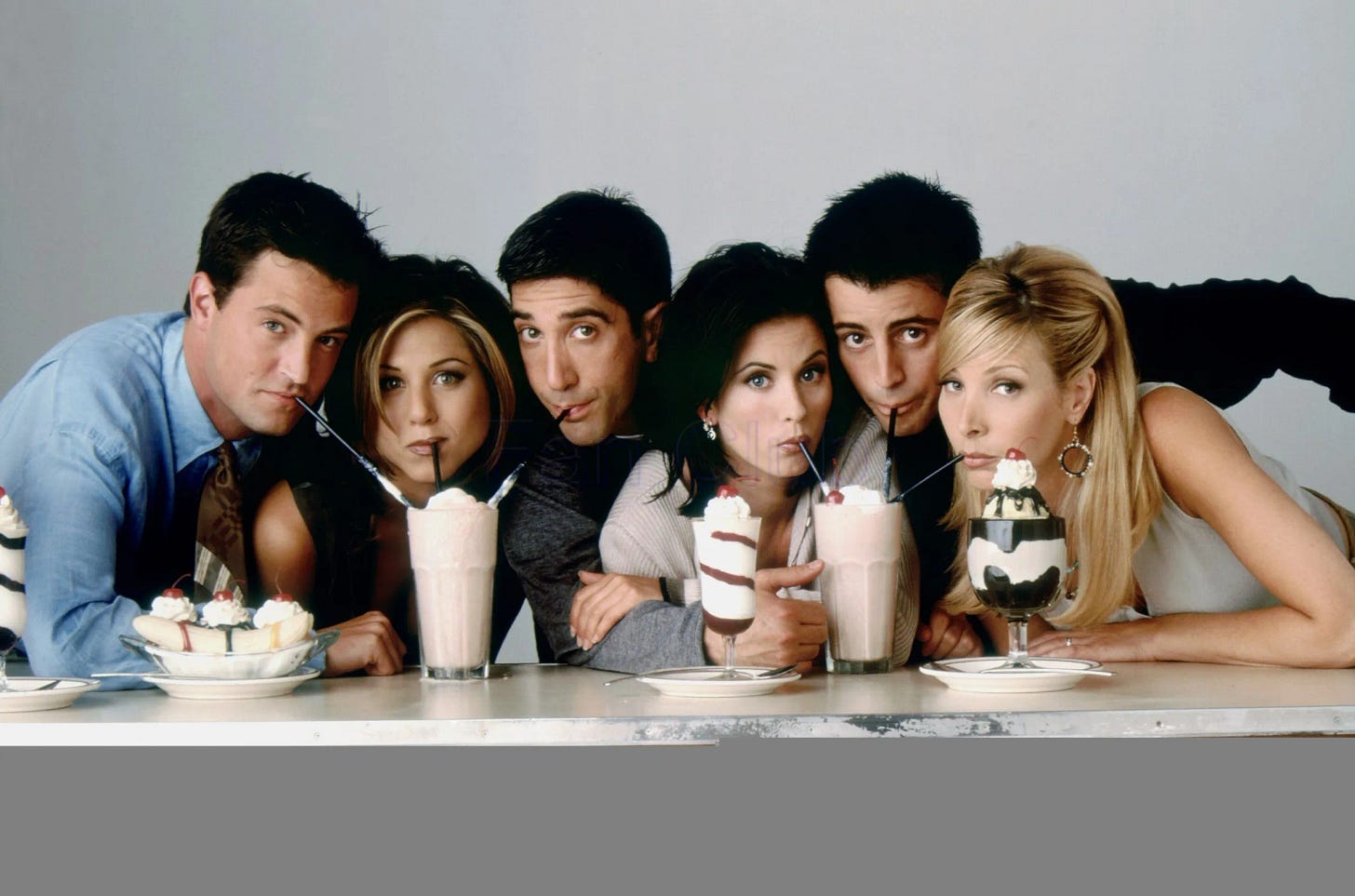

Before we get into the prompts, I wanted to ask you a question. Who is the main character of Friends?

Okay, why am I asking this? I’ll tell you.

I once got into an argument (unwittingly) in the comments on TikTok about this one, and that is because the editor who created the video said that, according to the writers of Friends, Monica is “the main character,” or the central person around whom the show was based. And the reasoning was that Ross is her brother, Phoebe was her old roommate, Chandler and Joey are her friends, and Rachel is her old best friend. Okay, fair enough, and who am I to argue with the people who wrote the sitcom? Well, actually (hehe), I AM going to argue!

In my opinion, Rachel Green is the main character of Friends. The reason I believe this is because in the very first episode of the show, Rachel is the eyes we as the audience see through - she is running away from her life, and into the world of Friends, and it is through her that we discover the rest of the characters, and learn about the world.

You will notice a lot of books, TV shows, and movies begin this way, and this is sometimes called the “fish out of water.” Joel enters community college in Community, and we discover the world of the college through his eyes. Jessica Day needs a new apartment and finds a home with the boys of New Girl, and we learn all about them and their lives through her.

For a literary reference that will be familiar to many, when we read The Great Gatsby, we are finding out the story through the eyes of Nick Carraway, who has just started a new job and is renting a new home on Long Island, next to the titular Gatsby.

This way of entering a story, through the eyes of a character who is new to the events, is popular, because it gives a reason for the point of view character to explain, in scene, what is happening and how they perceive it, and to become a place for the characters who were “already there” to tell their sides of the story. If Daisy was the narrator, it would be a different book, because she would tell us from the beginning that she was in love with Gatsby once, but he was too poor for her, and she married someone rich who cheats on her and makes her miserable, but she won’t leave because they also do love each other in a way and he provides the life she always desired even with its imperfections. But Nick has to piece this all together, and more, through his conversations and observations with the various characters.

Another way of entering a story is the frame story. Their Eyes Were Watching God and Wuthering Heights employ this method, in which a character starts in the present, tells the story of the past, and ends in the present. Do you see how, in the literary examples here, the structure and the point of view are intertwined?

While working on your outline and prewriting, you’ll want to think of the point of view early on. Here are some questions to help brainstorm the perfect point of view (POV), and by that I mean not just the person telling the story, but the ways they are telling it.

Who is telling the story? A character from inside the story or a narrator outside of it all? If it’s a narrator outside of the story like in Wuthering Heights, how did they come to learn the story? If it’s a character from within the story like with Their Eyes Were Watching God, at what point did they enter the story? Is your character or narrator an observer or participator, or an observer who gets drawn into participating (like Nick Carraway)?

Weigh the differences between first person, third person limited, and third person omniscient. How “in their head” do you plan to go? How much do you want the reader to know, and what do you want to hide?

What is the tense? Present tense, or past tense? Why did you choose the one you chose? Does it feel natural to you as the writer?

What kind of language does the narrator use? Complicated, “big” words? Or simplistic language? This can help the reader think about the culture and education and background of the character.

After you think about all this, and you’ve narrowed down their perspective and POV, please read about authority, archetypes, and voice here.

Genre

Genre is a complex beast. It seems simple and obvious, but it’s not. Because genre isn’t just about writing in the category you prefer (though that is a factor!), it’s also about which genre best serves the story.

For example, if you want to write about big societal issues, you have some choices depending on what those issues are.

Do you want to zoom in on one character and write about the minutiae of their day, in a way that is subtle regarding those societal issues?

Or do you want to write a big sci-fi novel which takes these issues and shows them through society as a whole?

That isn’t to say the first example can’t be written as sci-fi as well. But the genre and the topic you’re writing about are like a kaleidoscope. There are endless ways to combine genre with story, and it helps to think of genre as a container rather than something that is boxing you in.

I think what’s important to note about genre is that it can affect how experimental you want to be with the structure.

Here are some questions about genre to get you started.

What genres do you like to read and why?

What genres are you comfortable writing in? Is there a new-to-you genre you’d like to try?

More importantly if working on a specific project, what genre(s) might best support your characters, their journey, and the plot?

Can you name a few books or tv shows that changed your perspective on genre or challenged you in some way, or inspired you with their use of genre?

Can you borrow from other genres even if you are writing literary fiction?

I think genre is very personal. For years, I tried to fit myself into a literary fiction box because I thought that was the genre I was supposed to write in. But when I realized that science fiction, a genre I’d long avoided, was the right vehicle to tell some of my stories, my writing world opened up!

So think about the boxes you’re putting yourself into and how you can open your writing world, if that’s something that resonates with you. Perhaps the key to unlocking your next level is within a place you haven’t yet dared to go.

Structure

Many of us might be familiar with the “three act structure,” or even the four act structure, or “Save the Cat,” or other popular story skeletons. Those are great, and they are useful, but there is a caveat: don’t let them limit you, as they are the bare-bones starting point, not the place you need to be in the end. Understand as well that many of these are Western World Structures and storytelling doesn’t work that way in many parts of the world. Do with that information what you will.

So why do your POV and genre determine structure? The structure can be a big part of worldbuilding if you let it. The way the narrator tells the story can contain big clues about who the narrator is and the time and place they are living in.

A story told in verse, stream of consciousness, non-linearly, or an epistolary format (for example, in letters), or an interactive format, has different asks of the reader than a story told in a linear format. How engaged do you want them to be beyond reading? Some readers may want to be as involved as possible, or to learn about different people and cultures, and others may be reading simply to escape and not do any “work” at all. All genres are valid, all structures are valid, but it’s important to think about their purpose for your particular project.

Some ways to get readers EXTRA involved might include:

Choose Your Own Adventure (this has been done for adults too!)

A book that involves ephemera such as physical “letters,” flaps, and “notes” in the margins written by characters

Footnotes, if your story will actually benefit from it

Having a story that gets so blown wide open with revelation, it begs to be read multiple times - an example of this might be Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, or Lois Lowry’s The Giver.

Attempt at your own risk ;)

Other things to consider regarding Structure

Will you write linearly or non-linearly? Will you format the final manuscript as linear or non-linear? I think this depends partly on what you want to reveal and when.

Do you plan to tell the story from the perspective of one character, or multiple? If multiple, how many? Why is each perspective (if more than one) necessary? How do they add to or play off each other?

Are you dealing in scenes, chapters, or parts? Will you write them that way, or will you put it together that way in the end? (This is a chance to think about your process).

I used to think of structure, genre, and point of view as only intuitive. But intuition plus intentionality is powerful AF, and we can absolutely achieve balance between writing with a goal in mind, and writing with the goal of surprising even ourselves.

I hope your writing hand hurts (she says, lovingly).

I really want to hear your thoughts! Comment below, where in the writing process do you thrive, and where do you have trouble? Do you see any particular “separate” pieces of craft as moving parts that work together?

Until next time!